On one of my first visits to Italy, in the late 1970s, Paola introduced me to her grandmother. Nonna Maria spoke no English and I had learnt just a few phrases of Italian, but we smiled at each other and I learned afterwards that the matriarch had pronounced that I was a ‘ragazzo per bene’ – a suitable boy.

Nonna Maria died a few years later. Paola and I were married in 1978 and spent the following forty years living and working around the world. A couple of years after retiring we decided to look for somewhere warm to spend the winter months. We focussed on Liguria, the Italian riviera, which extends on either side of Genoa, from Ventimiglia at the French border, to Cinque Terre in the South. Paola’s brother and several cousins lived here, and her nonna Maria had originally come from Genoa, or so I thought.

In autumn 2022 we drove from Belgium through Switzerland to Italy and began our search for a suitable winter home. I had only one condition: that there should be a golf course nearby. I am addicted to the game, and sport is a great way to make friends in a new country. We found an excellent course in Garlenda, but it was not particularly welcoming. Golf is still an elite sport in Italy, with the associated golf snobbery. We travelled from the Ponente (sunset) side of Liguria to the Levante (sunrise) side and spent a week in Lerici, on the beautiful Bay of Poets, which Shelley and Byron visited in the 19th century. The sunsets were spectacular, but there was only a miniature golf course.

However we found a more promising 18 hole golf course in Rapallo, a town which was also once frequented by poets – W.B.Yeats and Ezra Pound held court there in the 1920s. I made up a three ball with two club members who had recently retired from Turin and Milan. These gentlemen were good company, not over fussy about the golf, but, like most Italians, obsessed with food. After the 14th hole they enquired if I was not hungry and suggested that we adjourn for lunch, as the kitchen was closing soon. Over a tasty dish of spaghetti, and a good bottle of wine, we chatted about the essential criteria for a winter home. They recommended that I avoid small touristy places which would be dead in December. Instead they suggested I should consider nearby Chiavari, a town with a large local population. Many people from Chiavari emigrated to South America, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, where they made their fortune. On their return to Chiavari, in the 1930s, they constructed palazzi on wide avenues with names such as Corso Buenos Aires or Corso Montevideo. In Chiavari I might find an apartment in one of the palazzi from that era to renovate.

When I told Paola about my conversation with the golfers, and suggested that we try Chiavari, she consulted her relatives. They pointed out that Chiavari was in fact Nonna Maria’s birthplace. She had lived in the city until, aged seventeen, she eloped with Paola’s grandfather. (He was already married, with several children, but that is another story.) So Paola was happy for us to explore Chiavari, where she had family roots.

We found a friendly B & B and liked the feel of the city. There was a marina,with sailing boats, and a wide seaside promenade which offered regular saffron sunsets. In the town ancient narrow streets, bordered by colonnades, were packed with little shops. Even in December Chiavari was full of people walking up and down the Carrugio, chatting in groups or having coffee.

We viewed a few apartments, but found nothing exceptional, until I came across an agency specializing in renovations. They took us to visit a palazzo built in the 1930s. Over the entrance was the figure of a sailing ship, cast in iron. We climbed up marble stairs to a third-floor apartment and were struck by the entrance hall with its Art Deco tiled floor. The house was owned by a family once famous for the manufacture of tiles, and in each room the floor had a different pattern. Part of the apartment was being used as offices and there was little furniture. The main room was bright, facing South. I looked out to palm trees and the marina, and beyond a myriad of little boats sailing on a shimmering blue sea. I could imagine us settling in this place, and so could Paola.

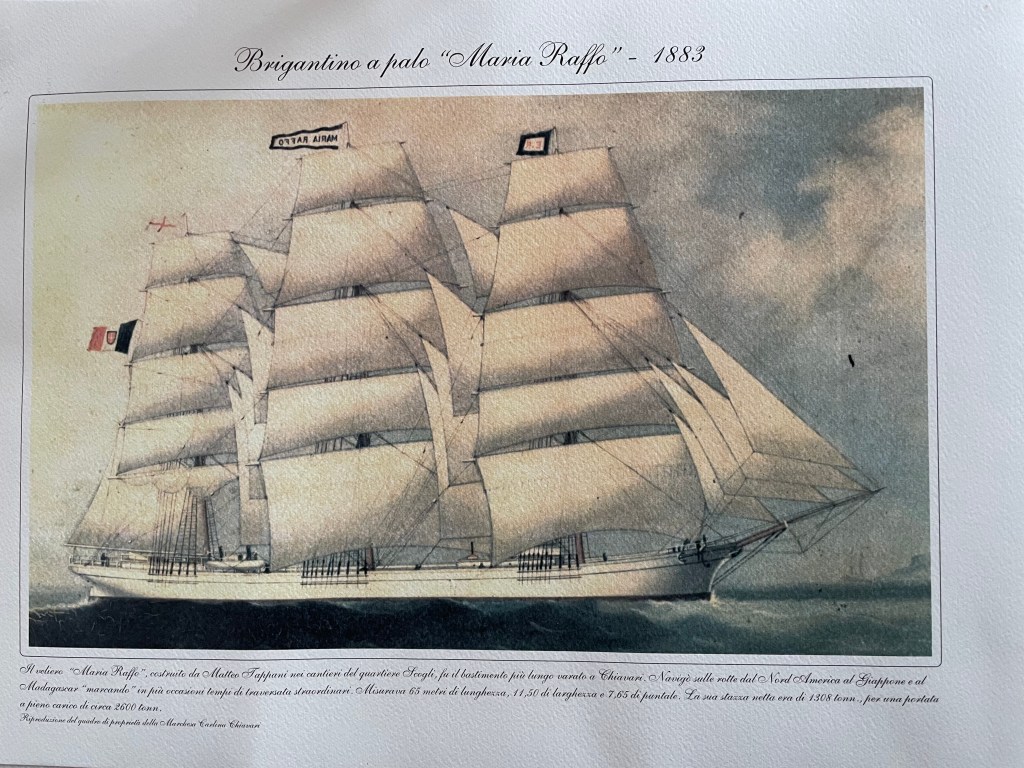

Turning away from the view, my eye was caught by a framed picture lying abandoned in the corner of the room on an old sideboard. I walked up to have a closer look. The picture was a drawing of a three-masted sailing boat, a Brigantine, and written in italics at the top was the boat’s name.

The boat was called the Maria Raffo, which is the full maiden name of Paola’s grandmother, nonna Maria Raffo.

This was a sign, a blessing from nonna Maria. We looked no further. We bought the flat, renovated it, and are living in it two years later.

At Christmas Paola gave me a copy of the Maria Raffo drawing which you can see below. The boat was built in Chiavari in 1883 for the shipowner Ernesto Raffo. It was remarkably fast and resistant in storms. For many years it carried goods across the Pacific Ocean, from the US to Japan, breaking records for speed. We have not yet discovered the link between Paola’s grandmother and the boat. Perhaps Ernesto Raffo named his boat after his wife. Was she a relative of Paola’s grandmother ? Whatever the precise history, these days Paola feels quite at home putting down new roots in Chiavari, the city of her grandmother, where everyday, as she goes to market and gets to know the inhabitants, she is no doubt meeting people to whom she is in some way related.

You must be logged in to post a comment.