As I close one decade and enter a new one, I ask myself whether it is better to revisit familiar places or to explore new horizons. Is it more rewarding to travel back, and learn what has changed and what remains, or to set out on a fresh adventure and be surprised by the new? One way to enjoy both old and new worlds is to visit places you know about but have never properly visited. So I have come to Greece for my 70th birthday celebrations.

I find Greece a wonderfully hospitable country. Each of our friendly guides asks us the same three questions: What’s your name? Where do you come from? Have you been here before? Well, I have been here, but my previous visits have been two and far between: a stifling night in a hotel in Piraeus in 1978, returning from my wedding in Tanzania, and a week on the island of Corfu in the 1990s, when we exited the Club Med once for a half day tour.

If academic studies were an accurate guide to destiny, I would have spent more time in Greece. Ancient Greek is my third foreign language, after French and Latin. My investment in the first two languages has already paid off well. I spent much of my working life in francophone countries, and now, in retirement, I’ve enjoyed almost six months in Italy, where they speak a modern version of Latin. So why haven’t I spent more time in Greece?

Greece in early spring is as beautiful as it is supposed to be. The birds are singing, and wildflowers explode under the olive trees. The poppies are a deeper more blood-red colour than those showing their first growth in my Edinburgh garden. A few days ago, in the blue and white seaside village of Galaxidi, I listened to the water lapping on the shore and watched as “rosy-fingered dawn” appear over Mt. Parnassus. My thoughts turned to the Odyssey, taught to us by the late Michael Longley, to Odysseus and Telemachus, and then to my son David running at the same moment across England from West to East. We too also crossed mountains, the snow-covered Pindus range, not on foot but in a jeep. For a few hours, in that remote part of Greece, close to Albania, we were well away from the madding crowd of other tourists.

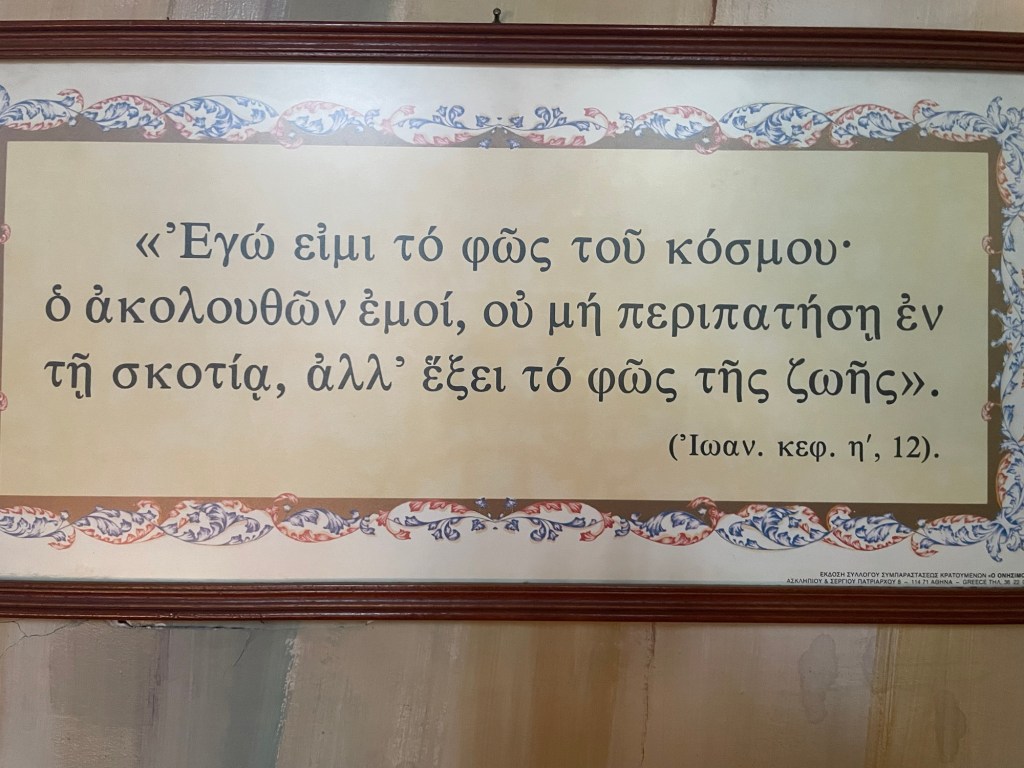

Before this visit I already knew much about this country’s history, culture, and religion. For two years in the mid-1960s I was one of a small band of pupils who chose to study Ancient Greek, and obtained two O-levels—one in the language and one in the Greek New Testament. The Good Book was first written in Greek, as I was reminded when we visited Corinth, and saw where St. Paul faced his accusers. When I was fifteen I was able to translate the entire Gospel according to St. Mark into English. It helped that I was well-versed in the English text.

When we visited the Acropolis on my birthday, and posted a picture to prove it, one of my Facebook friends remarked that this was a ‘confluence of ancient ruins’. Ha ha, Dave. I had a similar thought, but kept it to myself. Good word ‘confluence’, but of Latin origin. I would prefer ‘synchronization’ from the Greek, meaning ‘in time with’.

From that vantage point, high above the city of Athens, we looked down at the theatre where Sophocles’ tragedy Antigone was first performed. I thought of our teachers, Old Rothers and Charlie Fay. It is the only play I have ever performed in —in both Greek and English—hiding my nerves behind a giant mask of the Chorus.

Of course, today there is the slight problem of updating my knowledge of Ancient Greek to Modern Greek. Judging by their puzzled reactions, today’s Greeks have difficulty understanding their own archaic tongue, particularly when spoken with a Belfast accent. Over the last two millennia some vowels have shifted, and some consonants have clustered in confusing ways.

Notwithstanding these impediments, as I travel through this country I feel that the Greek language insurance policy I took out fifty years ago has finally matured. It is satisfying to be able to decipher and make sense of the characters of the 24-letter Greek alphabet. In a restaurant, this reveals the simplest words for potatoes and tomatoes. Along the highway, I discovered the place name Thermopylae, just in time to ask the driver to stop at the battlefield where the ancient Spartans made their last stand. And in the amazing monasteries of Meteora I was able to decipher the biblical texts on the walls. Each small success — with menus, the names of streets, or scripture— gives me the simple joy of connecting with ancient and modern people through a shared language.

You must be logged in to post a comment.