The first time I saw Bob Dylan was in Belgium in the 1980s, at Anderlecht football ground. His band occupied a stage at one end of the pitch while we stood at the other. We could scarcely see him nor make out the songs he was singing, so distant was the band and so successfully did Dylan disguise his well-known words and tunes.

The second time was at a concert was in Uruguay in 2006, at the Conrad Hotel in Punta del Este. The audience was made up of rich young Argentinians on holiday, calling their friends by mobile phone and then waving to one another across the stadium. I strained to listen Dylan singing “Like a Rolling Stone”, one of the anthems of my youth, but the Argentinians paid little attention. They were a different generation. For them it was all about being seen in the right place, and they spoiled my experience.

When I learnt that Dylan was playing once more in Brussels, this time in the intimate and beautiful Palais des Beaux Arts, I didn’t think twice. He is now 84 years old – no spring rooster crowing at the break of dawn. We bought tickets and travelled from Italy to Brussels for the concert.

What attracted me most to this concert was that it was without phones. Dylan had decided to disarm philistines and hangers-on, people addicted to capturing images that they will look at once and then discard. He seemed to be caring for genuine fans like me. At last, I might hear the world’s finest song-writer close-up and without distractions. In his heyday Dylan was a mighty poet, not read in school-books but listened to on the radio, on TV, a troubadour singing for the poor and dispossessed, for freedom, for the whole world. There were other great singer song-writers – Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell and Van Morrison, but Dylan soared above them all. And maybe, in 2025, with his new-found concern for the quality of the audience’s experience, he might even reward us with recognizable versions of his greatest hits.

We arrived at the Bozar an hour early, before the Art Deco entrance doors were unlocked. Our phones were locked away in pouches resembling church money collection bags, except that we allowed to carry them with us. We now had an hour to wait, time to sip a glass of wine and watch as people of all ages walked into the concert hall and stood around. Hundreds of people were happily talking to one other. No heads were buried, fixed on screens, communicating with people elsewhere. We were all together, fully present in the same public space.

With fifteen minutes to go, we took our seats in the “baignoires” – boxes like old-fashioned baths, just twenty yards from the stage. This was the closest I had ever been at a Dylan concert. The hall was packed, buzzing with anticipation, the bells ringing for ten minutes to go and then five, until, right on time, a group of ancient musicians, dressed in black, appeared on stage. I was reminded of when we used to wait on the Lisburn Road in Belfast for the bands to arrive on 12th July: all of us looking down the road waiting and listening for the music to begin.

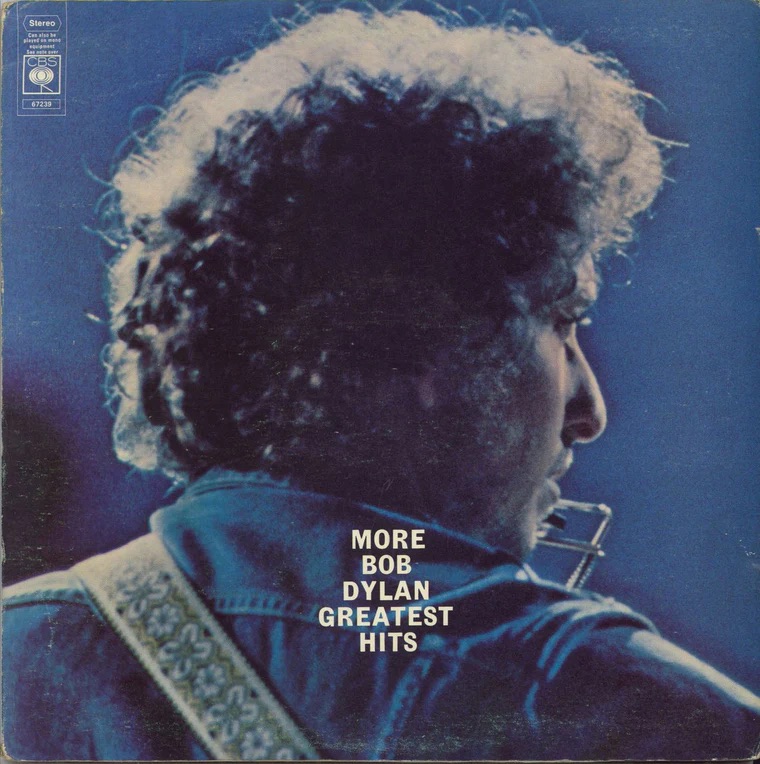

The lights were yellow and low. Dylan, surrounded tightly by his band, started with his back to the audience. The first song brought tears to my eyes. “I’ll be your baby tonight” was on the double LP Greatest Hits 2 which my brother John and I bought for Christmas in 1973. We listened and danced to this music in John’s room until the record player needle broke. It was harder to recognize “It ain’t me babe”, the only one of his early songs that Dylan played. A protest song of sorts, both a personal and public one. He was once more reminding us that he is only the poet, not the leader, not the messiah.

After that it got harder to make out the words in Dylan’s octogenarian guttural growl. I refused to believe Paola when she whispered to me he was singing “When I paint my masterpiece”, perhaps my favourite Dylan song. The tune was different, the rhythm was samba, but she was right. We made out the words “I left Rome and landed in Brussels” and a cheer broke out across the Belgian audience.

Most of the other songs were new – well, new to us. We have not kept up with the 50 plus albums Dylan has brought out in his lifetime. Dylan still seems to enjoy singing the songs he chooses on the night, not the songs the audience wants to hear. He and his band played without a break for eighty minutes. Chapeau ! From time to time he stood up for a few seconds and then sat down. He left the stage with no goodbye, thanks or encore, but we felt that he had given us good value.

In 1964, at the height of his fame as a folk singer of protest songs, Dylan closed the album “The Times They Are A-Changin’” by taking “The Parting Glass”, a traditional song that he got from the Clancy brothers, and transforming it into “Restless Farewell”. It was a rebuke to critics of magazines like Newsweek who sought to tie him down, to know who had influenced him, and what cereal he ate for breakfast. The song ends with the lines:

‘So I’ll make my stand

And remain as I am

And bid farewell and not give a damn’

Robert Zimmerman did not disappoint us this time. His idea to lock up our phones made all the difference. And I found it reassuring that he still presents his audiences with an enigma: A complete unknown/With no direction home/like a rolling stone.

You must be logged in to post a comment.